In Azure you have two main ways of managing your virtual network connectivity: self-managed hub-and-spoke and Virtual WAN. Virtual WAN is a solution where Microsoft manages part of your virtual networks for you, and in exchange it gives you some benefits such as any-to-any routing out of the box.

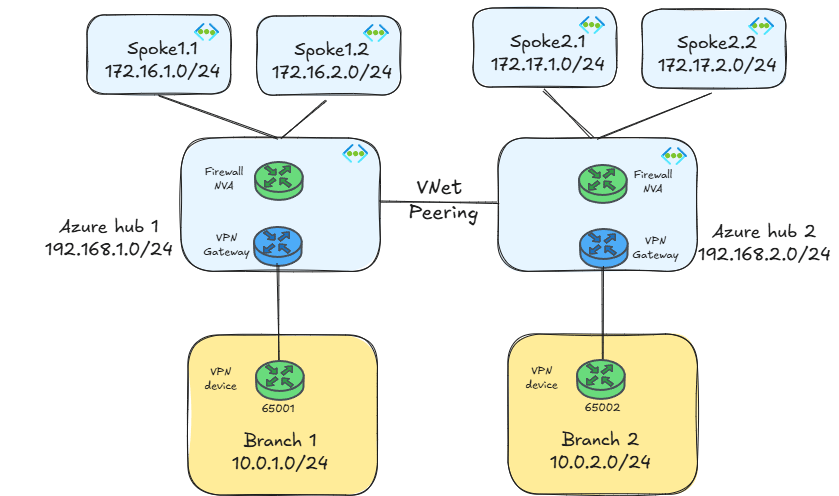

However, what if you need that any-to-any routing, but you still need the flexibility that the self-managed hub-and-spoke model gives you? This is going to be the topic of this post, where as test bed I will use this topology:

By the way, if you already guessed why I am using hub IP ranges that do not overlap with the spokes, you probably know what I am going to talk about here. Otherwise, keep reading, this mystery will be cleared up further down.

As you can infer from the figure above, I am using IPsec VPNs as hybrid interconnection technology with BGP, but the main techniques explained in this article will be applicable as well to ExpressRoute connections.

I am using as well an NVA as a firewall. This is important because in some of the designs explained in this blog BGP will be needed. If using Azure Firewall (which doesn’t support BGP) is a mandate, you could use the workaround I describe in Azure Firewall’s sidekick to join the BGP superheroes.

As a last remark, if you are using NVAs you would probably have at least two instances in each region for redundancy front-ended by an Azure Load Balancer. Again, that will not change the main concepts of the designs explained in this post.

Spoke-to-spoke

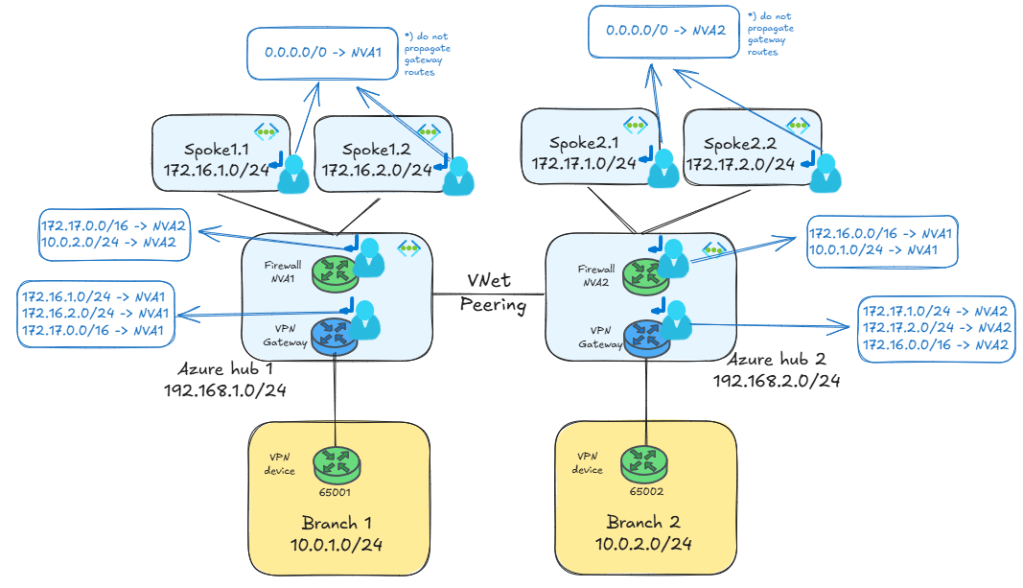

The first requirement of any-to-any connectivity is providing communication between spokes located in different regions. This is not hard to implement, since the only thing you need is route tables in your spoke and your NVA subnets:

As the previous figure shows, the route tables associated to the spoke subnets are the same as for classic hub-and-spoke deployments, a default route with the local firewalls as next hop will be enough. It is important to disable gateway route propagation in the spoke subnets, otherwise they would import the more specific gateway routes and bypass the firewall for traffic going to the branches.

If I do a traceroute from a virtual machine in spoke-11 to another one in spoke-12 using the Linux tool mtr (I strongly suggest to wipe your mind and forget that you have ever seen something called traceroute), I can see that the traffic is traversing both NVAs to get from one region to the other:

My traceroute [v0.95]

spoke11-vm (172.16.1.4) -> 172.17.1.4 (172.17.1.4) 2024-12-03T13:51:39+0000

Keys: Help Display mode Restart statistics Order of fields quit

Packets Pings

Host Loss% Snt Last Avg Best Wrst StDev

1. 192.168.1.36 0.0% 18 1.6 1.7 1.2 2.8 0.4

2. 192.168.2.36 0.0% 18 3.2 3.4 2.2 5.7 1.0

3. 172.17.1.4 0.0% 17 4.3 5.0 3.6 7.8 1.3

Spoke-to-branch

Alright that was easy. What about going from one spoke to a branch in a different region? This is a tricker problem, since it now involves the Virtual Network Gateway (VNG) too. Consequently, an additional route table is required in the GatewaySubnet, plus additional routes in the NVA’s subnet:

The additional routes in the NVA’s subnet tell Azure how to route traffic for the remote region(s). If you did your IP address design correctly, you should be able to summarize your routes. For example, in the design above I can summarize all the spokes in region 1 as 172.16.0.0/16 and all the spokes in region 2 as 172.17.0.0/16. Consequently, the effective routes in the NVA look like this (in this example the NVA in region 1):

az network nic show-effective-route-table -n nva1VMNic -g $rg -o table Source State Address Prefix Next Hop Type Next Hop IP --------------------- ------- ---------------- --------------------- ------------- Default Active 192.168.1.0/24 VnetLocal Default Active 192.168.2.0/24 VNetPeering Default Active 172.16.1.0/24 VNetPeering Default Active 172.16.2.0/24 VNetPeering VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.4/32 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.4 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.4/32 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.5 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.0/24 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.4 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.0/24 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.5 Default Active 0.0.0.0/0 Internet Default Active 10.0.0.0/8 None ... Default Active 20.35.252.0/22 None User Active 172.17.0.0/16 VirtualAppliance 192.168.2.36 User Active 10.0.2.0/24 VirtualAppliance 192.168.2.36

However, the network device in branch1 will not know how to reach the spokes in region 2, since the VNG only advertises the directly connected spokes of region 1:

jose@branch1:~$ ip route

default via 10.0.1.1 dev eth0 proto dhcp src 10.0.1.4 metric 100

172.16.1.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

172.16.2.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

192.168.1.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

So the crux of the problem is how to let the branch1 appliance know that it can reach 172.17.0.0/16 through the VPN tunnel too.

Option 0: connect each branch to all hubs

The quickest and simplest way of doing something is… not having to do it in the first place. This is why Microsoft’s recommendation is usually connecting your branches to all hubs, either using VPN site-to-site tunnels or ExpressRoute circuits. In our example you could do this with a couple of an additional site-to-site tunnels:

In this design branch1 would obviously learn all Azure prefixes: it would learn the 172.16.x.0/24 prefixes from the VPN gateway in hub 1, and the 172.17.x.0/24 prefixes from the VPN gateway in hub 2, so branch1 would have access to Azure VNets in all regions.

In the case of IPsec VPNs, creating a couple of additional tunnels has very little impact to the total cost of the solution, and can greatly simplify the spoke-to-branch routing design. If you are using ExpressRoute, adding those cross-connections might have a higher impact, since it means using Standard circuits (see my post about this ExpressRoute multi-region: triangles or squares?).

If you are 100% decided not to have those cross-connections, keep reading!

Option 1: static routes

Back to our problem. If branch1 doesn’t have routing for spokes in remote regions, the obvious choice is adding static routes. Since my branch1 device is actually a Linux box, here how I could add routes to let it know about the spokes in region 2:

ip route add 172.17.0.0/16 dev ipsec0

Since this is an IPsec VPN, the next hop is one of the virtual tunnel interfaces. Note that this is suboptimal if you have two tunnels (if the Azure VPN gateway is running in active/active mode), since this configuration wouldn’t load balance traffic over both tunnels, and would suffer from an outage if the tunnel on ipsec0 failed, even if the second tunnel stayed up.

Now that branch1 has routing for the spokes in region2, we can try to reach branch1 from a virtual machine in the virtual network spoke21. As the mtr output shows, connectivity is going through both firewalls, as it was in the case of spoke-to-spoke:

My traceroute [v0.95]

spoke21-vm (172.17.1.4) -> 10.0.1.4 (10.0.1.4) 2024-12-03T14:15:45+0000

Keys: Help Display mode Restart statistics Order of fields quit

Packets Pings

Host Loss% Snt Last Avg Best Wrst StDev

1. 192.168.2.36 0.0% 14 1.1 1.6 1.1 2.3 0.3

2. 192.168.1.36 0.0% 13 2.8 3.1 2.3 4.5 0.6

3. 10.0.1.4 0.0% 13 5.3 5.9 4.8 9.6 1.2

The Azure VPN gateways do not show up in your traceroute output, but that is normal: Azure Virtual Network Gateways do not decrease the TTL field in IP packets, so they are essentially invisible to traceroutes.

One important aspect of static routing is that it will not work for ExpressRoute circuits: in ExpressRoute you have additional devices in Microsoft’s backbone that need to be aware of the remote prefixes, so using BGP is a requirement so that the whole data path gets the correct routing information.

Option 2: Route Server

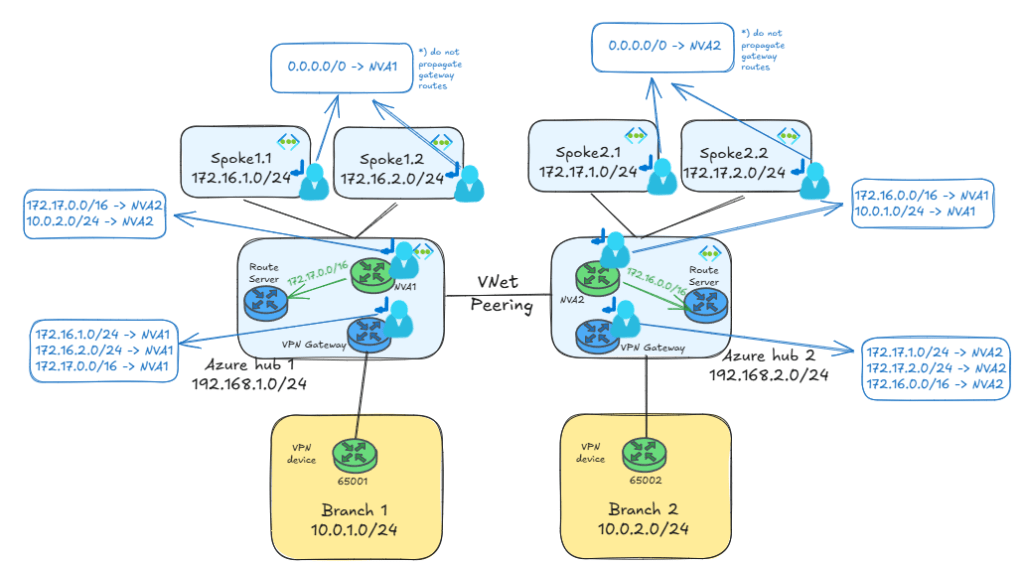

What if you wanted to avoid static routes in the branches (especially if you have many of them) and force the Azure VPN gateway to advertise the prefixes of the remote spokes?You can use Azure Route Server to inject routes via BGP towards the branches:

The Azure Route Servers in each region need to be configured with the setting branch-to-branch routing enabled, otherwise they will not form BGP adjacencies to the Virtual Network Gateways. You can check the BGP neighbors of the VNGs with this command, which in the example below for VNG1 shows both ARS instances (192.168.1.68 and 192.168.1.69) as BGP neighbors of each of the VNG instances (I have introduced an empty line break between the output for each VNG instance for readability):

$ az network vnet-gateway list-bgp-peer-status -n vpngw1 -g $rg -o table Neighbor ASN State ConnectedDuration RoutesReceived MessagesSent MessagesReceived ------------ ----- --------- ------------------- ---------------- -------------- ------------------ 10.0.1.4 65001 Connected 02:28:43.3454739 3 178 183 192.168.1.5 65515 Connected 03:00:17.2650771 3 244 250 192.168.1.4 65515 Unknown 0 0 0 192.168.1.69 65515 Connected 00:37:14.4283540 2 53 56 192.168.1.68 65515 Connected 00:37:14.4283540 2 54 58 10.0.1.4 65001 Connected 02:28:43.9207249 3 178 182 192.168.1.5 65515 Unknown 0 0 0 192.168.1.4 65515 Connected 03:00:17.4688309 3 248 246 192.168.1.69 65515 Connected 00:37:17.3730231 0 53 57 192.168.1.68 65515 Connected 00:37:17.3730231 0 54 57

After the NVAs advertise the routes to ARS, it will send them to the VNGs. Here the routes the VNG instances in hub 1 learn (again with a line break between the outputs corresponding to each gateway instance):

az network vnet-gateway list-learned-routes -n vpngw1 -g $rg -o table Network Origin SourcePeer AsPath Weight NextHop -------------- -------- ------------ -------- -------- ------------ 192.168.1.0/24 Network 192.168.1.4 32768 10.0.1.4/32 Network 192.168.1.4 32768 10.0.1.4/32 IBgp 192.168.1.5 32768 192.168.1.5 10.0.1.0/24 EBgp 10.0.1.4 65001 32768 10.0.1.4 10.0.1.0/24 IBgp 192.168.1.5 65001 32768 192.168.1.5 10.0.1.0/24 IBgp 192.168.1.69 65001 32768 192.168.1.5 10.0.1.0/24 IBgp 192.168.1.68 65001 32768 192.168.1.5 192.168.1.5/32 EBgp 10.0.1.4 65001 32768 10.0.1.4 172.16.1.0/24 Network 192.168.1.4 32768 172.16.2.0/24 Network 192.168.1.4 32768 172.17.0.0/16 IBgp 192.168.1.69 65501 32768 192.168.1.36 172.17.0.0/16 IBgp 192.168.1.68 65501 32768 192.168.1.36 192.168.1.0/24 Network 192.168.1.5 32768 10.0.1.4/32 Network 192.168.1.5 32768 10.0.1.4/32 IBgp 192.168.1.4 32768 192.168.1.4 10.0.1.0/24 EBgp 10.0.1.4 65001 32768 10.0.1.4 10.0.1.0/24 IBgp 192.168.1.4 65001 32768 192.168.1.4 192.168.1.4/32 EBgp 10.0.1.4 65001 32768 10.0.1.4 172.16.1.0/24 Network 192.168.1.5 32768 172.16.2.0/24 Network 192.168.1.5 32768 172.17.0.0/16 IBgp 192.168.1.69 65501 32768 192.168.1.36 172.17.0.0/16 IBgp 192.168.1.68 65501 32768 192.168.1.36

Once the VNGs learn the routes from Azure Route Server, they will advertise them over the IPsec tunnels. We can verify that checking that branch1 is now learning the 172.17.0.0/16 prefix, which was previously missing (of course, I removed the static route from “Option 1”):

jose@branch1:~$ ip route

default via 10.0.1.1 dev eth0 proto dhcp src 10.0.1.4 metric 100

172.16.1.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

172.16.2.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

172.17.0.0/16 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

192.168.1.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

We can have a look again at the route table at NVA1’s subnet, where you will see a static route for 172.17.0.0/16 with NVA2 as next hop. Having the exact same prefix in the UDR as the one advertised by the NVA is critical to overwrite the route that ARS would program in the subnet, otherwise you might have routing loops:

$ az network nic show-effective-route-table -n nva1VMNic -g $rg -o table Source State Address Prefix Next Hop Type Next Hop IP --------------------- ------- ---------------- --------------------- ------------- Default Active 192.168.1.0/24 VnetLocal Default Active 192.168.2.0/24 VNetPeering Default Active 172.16.1.0/24 VNetPeering Default Active 172.16.2.0/24 VNetPeering VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.0/24 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.5 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.0/24 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.4 VirtualNetworkGateway Invalid 172.17.0.0/16 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.36 Default Active 0.0.0.0/0 Internet Default Active 10.0.0.0/8 None ... Default Active 20.35.252.0/22 None User Active 172.17.0.0/16 VirtualAppliance 192.168.2.36 User Active 10.0.2.0/24 VirtualAppliance 192.168.2.36

We can do our connectivity test from spoke21 again, and verify that it can still reach branch1 over both firewall NVAs:

My traceroute [v0.95]

spoke21-vm (172.17.1.4) -> 10.0.1.4 (10.0.1.4) 2024-12-03T15:47:09+0000

Keys: Help Display mode Restart statistics Order of fields quit

Packets Pings

Host Loss% Snt Last Avg Best Wrst StDev

1. 192.168.2.36 0.0% 8 1.4 1.4 1.2 1.9 0.2

2. 192.168.1.36 0.0% 7 2.7 2.7 2.2 3.5 0.4

3. 10.0.1.4 0.0% 7 6.6 6.0 5.0 7.1 0.8

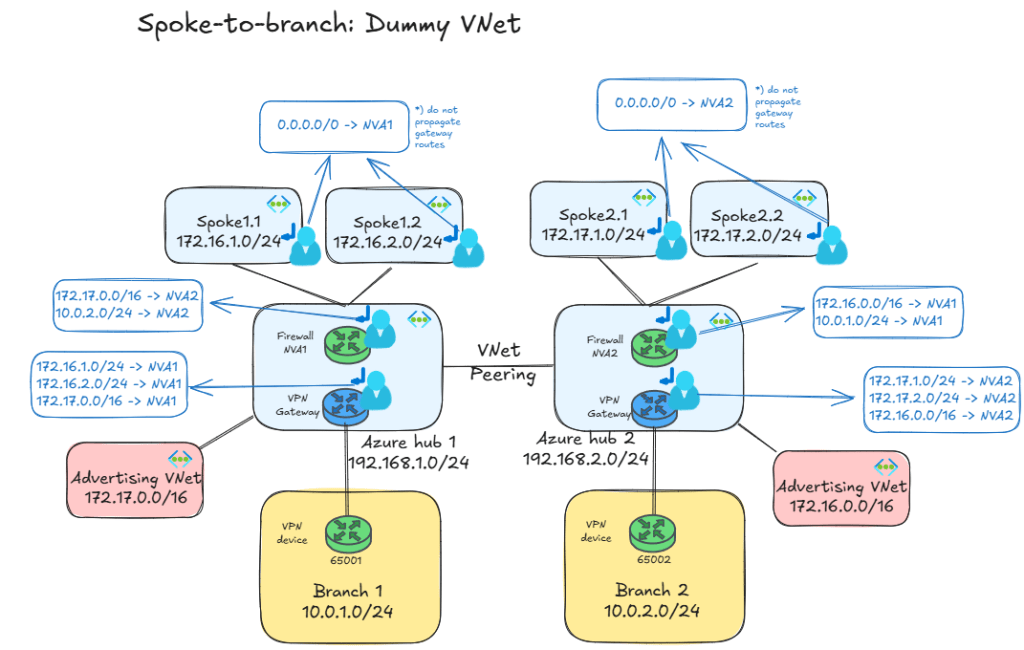

Option 3: advertising VNet

There is one last trick you can do to advertise prefixes over BGP from a VNG. You know that it will announce the prefixes of all VNets it is directly connected to, so you could create a VNet whose sole purpose is forcing the VNG to advertise a given prefix. Some call this VNet “dummy VNet”, “advertising VNet”, “summary VNet” or something of the like. Pick your favorite. The design would look like this:

You might have been wondering why I picked the hub IP addresses from a different range as the spokes. Well, I can finally unveil that mystery: if hub2 had been for example 172.17.0.0/24, I wouldn’t have been able to peer a VNet with 172.17.0.0/16 to hub1, since a given VNet cannot be peered to other two VNets if overlapping IP address space. Advertising aka dummy VNets would still have been possible, but you would have had to create multiple ones, not overlapping with hub2’s range.

After peering the advertising VNets with their respective branches, we can verify that branch1 is now getting the 172.17.0.0/16 summary over BGP without the need for any route server:

jose@branch1:~$ ip route

default via 10.0.1.1 dev eth0 proto dhcp src 10.0.1.4 metric 100

172.16.1.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

172.16.2.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

172.17.0.0/16 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

192.168.1.0/24 proto bird

nexthop via 192.168.1.4 dev ipsec1 weight 1

nexthop via 192.168.1.5 dev ipsec0 weight 1

Again, the exact prefix used in the route tables for the NVA and the VNGs needs to match exactly the prefix in the advertising VNet, so that the UDR invalidates the VNet peering system route:

az network nic show-effective-route-table -n nva1VMNic -g $rg -o table Source State Address Prefix Next Hop Type Next Hop IP --------------------- ------- ---------------- --------------------- ------------- Default Active 192.168.1.0/24 VnetLocal Default Active 192.168.2.0/24 VNetPeering Default Active 172.16.1.0/24 VNetPeering Default Active 172.16.2.0/24 VNetPeering Default Invalid 172.17.0.0/16 VNetPeering VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.4/32 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.4 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.4/32 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.5 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 1.1.1.1/32 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.4 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 1.1.1.1/32 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.5 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.0/24 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.4 VirtualNetworkGateway Active 10.0.1.0/24 VirtualNetworkGateway 192.168.1.5 Default Active 0.0.0.0/0 Internet Default Active 10.0.0.0/8 None Default Active 20.35.252.0/22 None User Active 172.17.0.0/16 VirtualAppliance 192.168.2.36 User Active 10.0.2.0/24 VirtualAppliance 192.168.2.36

Finally, the obligatory traceroute to verify that cross-hub from spoke21 to branch1 still works:

My traceroute [v0.95]

spoke21-vm (172.17.1.4) -> 10.0.1.4 (10.0.1.4) 2024-12-03T14:28:11+0000

Keys: Help Display mode Restart statistics Order of fields quit

Packets Pings

Host Loss% Snt Last Avg Best Wrst StDev

1. 192.168.2.36 0.0% 12 1.1 2.1 1.1 7.1 1.6

2. 192.168.1.36 0.0% 12 2.8 2.8 1.9 3.8 0.5

3. 10.0.1.4 0.0% 12 5.3 6.0 4.9 8.8 1.2

A couple of remarks here: is this a good idea? This is debatable: in static environments it might work, especially if you can summarize your spoke prefixes as in my example. However, in other cases you might have to change the prefix of the advertising VNet as you create additional VNets in your Azure regions (Update the address space for a peered virtual network will be very handy). Additionally, it introduces a level of complexity that the average Azure networking user might not be familiar with. However, it removes the BGP and Azure Route Server complexity, which might be a killer for some organizations. Whether this is the right approach for you or not, I would suggest to think twice before implementing this design option.

Option 4. IPsec between VNets

Another possibility to provide the right routing to the branches connected to the hub is connecting the gateways to each other, so that they exchange routes via BGP. If you only have VPN tunnels in the picture as in the example above, the solution could look like this:

As you can see, the VNet peering has been replaced by a connection between the two VPN gateways. This can be either VNet-to-VNet or a full-blown VPN configuration with Local Network Gateways, what would add the additional benefit of NAT support.

If you are using ExpressRoute the solution is a bit more complicated, since you would connect the VPN gateways to each other and you would need Azure Route Server so that the VPN gateways exchange traffic with the ExpressRoute gateways:

This method has a couple of caveats you need to be aware of:

- Traffic between regions will be encapsulated in IPsec by the VPN Gateways, with the subsequent limits on bandwidth that they will impose. The latest generations of Azure VPN gateways have increased bandwidth per tunnel, so this limit is getting less of an issue.

- Still speaking about IPsec throughput limits, if you run active/active VPN gateways on every hub you effectively have four tunnels between each pair of hubs, thus making that bandwidth-per-tunnel limit even less of an issue.

- A different limit you might reach is the number of routes per route table: Now every gateway will learn every VNet prefix, which you need to overwrite with User-Defined Routes in the Gateway Subnet. You can see in the diagram that the Gateway Subnet now need a UDR for each prefix. This means that you can have a maximum of 400 VNets over all regions if you follow this design.

- Because of every gateway knowing every spoke, whenever you add or remove a VNet in any region you need to update the UDRs at the GatewaySubnets in every hub.

Wrapping up

You saw three techniques for cross-hub spoke-to-branch communication:

- Static routing: only possible with VPN, not with ExpressRoute

- Azure Route Server: you need BGP-able appliances

- Advertising VNets: more of a hack actually, but this option doesn’t require BGP.

- IPsec between VNets: with some limits on bandwidth and scale, this is a good solution for small environments.

Hopefully this post convinced you of the inherent complexity of cross-hub, spoke-to-branch communication. If you can prevent this from being a requirement by connecting all your branches to all your hubs this will make your life a lot easier.

hi Jose,

how about replacing the vnet peering by vnet-to-vnet via von gateways? Thus, you wouldn’t have to deal this the complexity of route servers/NVA bgp configuration.

LikeLike

Very good point Robson! Let me add it as option to the post

LikeLike

Been thinking about that also, does the peering between hub here doest have any remote vpn option being chosen

LikeLike

Hey Munir! Not sure what you mean. I added a 4th option to the post, where you replace the global VNet peering between hubs with an IPsec tunnel. You would usually configure either one or the other, but not both.

LikeLike